Lean Media

It’s time to simplify digital media. The generational media gap. The happiest place on earth. Good jobs. And more.

Welcome to People vs Algorithms 22.

I look for patterns in media, business and culture. My POV is informed by 30 years of leadership in media and advertising businesses, most recently as global President of Hearst Magazines, one of the largest publishers in the world.

Get my free weekly email here:

TLDR

Digital media is highly efficient. Digital media businesses are not;

Opportunity to radically streamline the business to prioritize investment in the thing that really matters, the media product;

Long-standing advertising practices are much of the problem. As are ingrained operational practices and biases;

These are hard to change for incumbents. Creates opportunity for new Lean competitors;

The next wave will innovate content formats not platforms;

Change will only come by reengineering media strategies around high value niches and quality lists, endorsement driven content-based ad products…and a willingness to say no.

The Cannes Effect

“Because that’s where the money is,” was the reputed reply to a reporter's question as to why he robbed banks. Infamous bandit Willie Sutton’s response would eventually become known as Sutton’s Law, which basically says when trying to figure out what’s going on, look for the obvious. It took me a while to understand the obvious, but it eventually hit me aboard a yacht on route to lunch in St. Tropez.

It was about 10 years ago and I was, of course, at the Cannes Lion festival. It was a particularly spendy year in Cannes. I was reflecting on what seemed like pretty reckless expense account behavior but grateful to be the benefactor of it. Media companies spend a lot to influence the flow of money. It’s why Cannes Lion, in addition to being the prestigious industry gathering, is also the official festival of excess.

Overhead that particular afternoon, one of the years Microsoft was working very hard to be taken seriously as a media organization: “It's hard to keep up with the Microsoft guy’s largesse. It’s like they are bonused on the size of their expense accounts.” I asked for another glass of rose and pondered if this behavior was consistent with other industry gatherings. Did they spend this way at the annual ASHRAE (American Society of Heating Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers) confab?

Probably not. The obvious reason is media is a colossally inefficient business. To be clear, digital media itself is actually incredibly efficient, as media. Content can be created and distributed to an audience with no friction and very little cost. Logically, the more cost effective media becomes to create, the more lucrative it becomes to influence each incremental dollar of advertising into it. While two decades of innovation in adtech has sought to turn media buying into a hyper-rational and efficient automated auction process, the industry continues to spend lavishly not just to influence media buys, but to sell technologies and platforms promising to chase waste out of digital media buys. But everybody knows this. Tchin-tchin!

Read to the end for Good Job Alerts from Milk Street and Medallion

Digital media is a business of marginal economics — incremental revenue has almost almost no cost-of-goods. It is also a business of wildly imperfect information. As a result, lucrative purchase decisions are highly qualitative. Which is to say, millions of dollars of media spend representing millions of low cost revenue can be determined by subtle forces of personal persuasion. As in: “Hey, why don't you join us on a yacht to St. Tropez for an overflowing basket of the most expensive raw vegetables crudité you have ever dipped in divine anchovy dressing. The sand under the table is soft and warm on callused New York toes. I promise the rose will flow like the Euphrates.” This is Cannes persuasion.

The Lean Media Organization

My contention is digital media suffers badly from the Cannes effect. A lot of money is wasted that doesn’t make the product better, and despite all of the tech-led process innovation, there remains a cobweb of inefficiency — far too much of the P&L is dedicated to investment in how we distribute, package and sell. These decisions all make sense on the margin, but when you pull back, you will see opportunity for disruption.

What if you endeavored to engineer a media organization to be as efficient as possible, even if that involved tradeoffs that didn’t result in short term revenue optimization? How might you change thinking in an effort to maximize investment in the content product? It’s time to think about the Lean Media Organization.

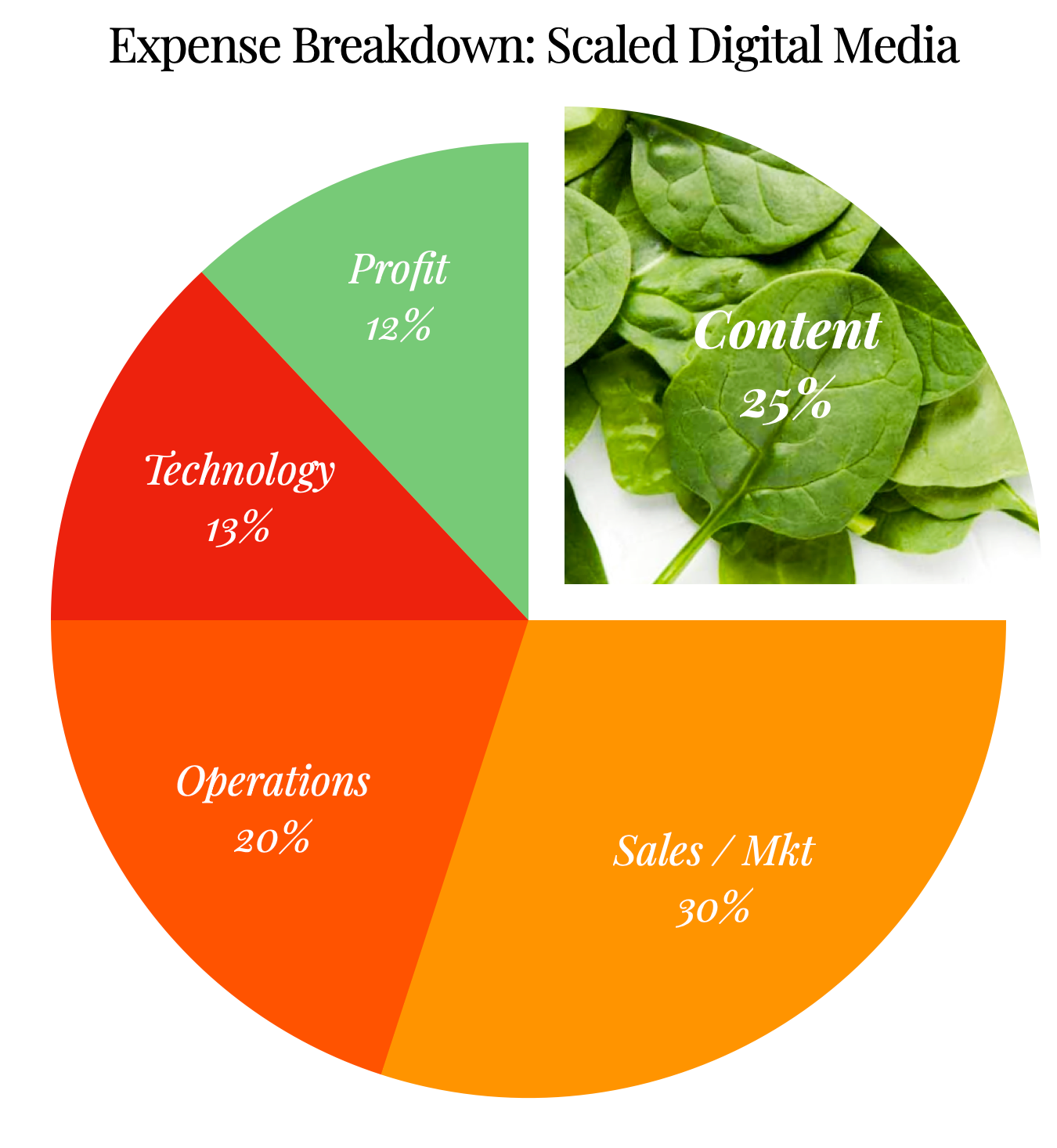

The big picture is this. The amount of money that finds its way to content is not unlike the music industry where, after all label expenses are factored in, an artist’s cut on revenue is a purported 12%. After budgeting for sales, marketing, operations, technology and profit, about 25% goes to content in digital media. The percentage would be far smaller if you account for leakage as money moves from the client to the agency and across a byzantine digital supply chain.

A typical digital media P&L would look something like the following:

To be clear I am describing a business that is predominantly ad driven — the profile changes when revenue mix shifts to subscription. The burden of running an expensive ad stack combined with the operational and technical complexity that sits downstream makes heavy demands on the business.

It shouldn’t be so complicated. Booking a vacation is easy now. So is buying stocks or paying a bill. Theoretically, so is buying online advertising. In practice this is not the case. You can readily book an ad with Google or Facebook. An online advertising auction marketplace was meant to streamline access to a broad set of inventory across the open web. But, outside of a performance-based ad buys, mostly through a handful of large platforms, huge complexity persists. I will spare you a deconstruction of the back and forth between client, agencies, publishers and an army of players in the middle managing impression integrity, targeting, measurement, ad creative, billing. Just know there’s a ton of people, process and expense involved. To quote a friend who is about as knowledgeable in these matters as you can get: “At every publisher the number of hands that touch the processing of a digital order is no different today than it was in 1999. Instead of a fax machine you use email attachment.”

Indeed, media buying remains highly custom and frustratingly qualitative. Every agency has their own process, there is virtually no standardization. A huge amount of time is spent preparing proposals and arranging “ad grids” to meet a buyer’s bespoke workflow. Agency side success often amounts to grinding “innovation” out of media companies under the guise of “I need to see something that has never been done before”, resulting in an exhausting time and people intensive RFP dance to win the deal. Publishers, ever willing, throw an endless number of bodies at the opportunity from across the org — sales, marketing, account management, data, creative, events, editorial — driven by the simple logic of marginal economics. In most cases, the ratio of sales support to sales person is about 3 to 1. The bottom line is win rates across the industry are below 20%, meaning 80% of the work done in the RFP hustle is wasted.

Complexity begins in sales, trickles downs to operations. Over the past 20 years, scaled publishers have sensibly invested in technology to manage the complexity of creating multiple content formats, integrating advertising, commerce and subscriptions, segmenting users, and syndicating that content to a diversified set of end points.

Layer upon layer of complexity emerged as the underlying distribution environment evolved. You built a site to deliver your content to the world but nobody came. You optimized for search bots and social syndication. You made content for Instagram and Snap, you sent feeds to MSN and Yahoo. You made video then audio then events. Very little had much to do with making better content. Most of it was about protecting the business from an over dependence on Google.

The investment was usually justified. Technically-oriented media owners and savvy growth hackers could amortize investment across a portfolio and successfully diversify ad-dependent businesses.

Now publishers want platforms to pay for more staff. Witness a recent battle waged successfully on Google and Facebook by Murdock and friends in Australia that inevitably will spread to more markets. Seems to me there’s something wrong with an industry when you have to beg Google to prop up your P&L.

I believe there’s a new structure on the horizon that will benefit lean, agile organizational architectures, a content-first approach that seeks to unwind much of the complexity that exists in the category. How might we engineer the business so the P&L looks more like this, where 50% of the budget is put into making the best possible content product?

I think the opportunity for Lean Media is now. We are beginning to see the emergence of new types of media organization structures characterized by:

Niche, opt-in audiences;

High value revenue structures that align with the content;

Disciplined organizational structures that leverage an array of off-the shelf technologies and people-efficient processes.

(Note: I could have called it something else but this made the most sense. As you would suspect, there’s a book on Lean Media, whose premise is connected but different. Its focus is optimizing for an iterative approach to media making, leveraging a minimum viable product, evolving with feedback from the audience, etc.)

This is more than creator economy stuff that I have gone on about in previous notes. The change is represented by a shift from low-yield, pageview-driven businesses to high-yield list based, expert-led ones. It embodies the spirit of creator media but will take shape in a variety of forms including new media brands that make room for personal brands and diverse points-of-view.

Reach vs. Relevance

The concept challenges a few key precepts of classic digital media. Lean is trust, relevance and influence…the opposite of “scale at all cost.” We all love the idea of “reach.” I have made the reach pitch constantly over the years, but it’s a tough sell for digital media. The internet’s power is niche. Subscription mechanics will define many of these businesses, but there will be very few subscription only businesses. Ads are not going away. And Lean only happens when we bring a materially different perspective to the ad offering. That, in turn, shapes the product. Media is always symbiotic.

The hardest part is saying no. No to the wrong revenue partnerships. No to build vs buy. No to anything that creates unnecessary overhead in the business that does not serve a specific audience with valued product. And the discipline to put every operational decision through the a lens of “can we find a simpler, lower-cost way to get the same result.” All told, it looks something like this:

Related, I suspect the same changes are slowly making their way through the agency ecosystem. You can certainly see the sentiment in Martin Sorrell’s reconstructed vision of the holding company with the mantra “faster, better, cheaper.” How this changes the mindset around media value and dysfunctional agency / publisher dynamic is TBD. But change seems inevitable.

Is this take a wee bit naive? Maybe, but that’s the fun part of having your own newsletter. Consider it food for thought.

The era of starting with a website is over. Now we start with a target community, a list and a format. And with a psychology of Lean.

Cannes takes place June 20-24. Book now and see how things work first hand. Just make sure the content team stays home and doesn’t see how the ad game really works.

Have a great weekend…/ Troy

(BTW, thanks to all who shared thoughts in last week’s survey. I found it very valuable. If you haven’t done so, please do.)

Why are young people out of their minds?

I was hanging out with The Professor this weekend. He was explaining the similarities between 60s and present day social tensions, suggesting that it has to do with “intragenerational” vs “intergenerational” communication patterns and underlying media technologies. It made a lot of sense to me. I asked him to write a couple of paragraphs for you. Thank you Professor!

Steven Pinker, in The Better Angels of our Nature, offers an account of the “decivilization” that occurred during the 1960s (first and foremost, the dramatic increase in violence). Obviously, the mere fact that the baby boom generation was so large was going to lead to increased violence and disorder, simply because most violence is perpetrated by young men. The effect was amplified, however, by the development of communications technology, primarily radio and television, that amplified intragenerational, and decreased intergenerational communication. The youth culture of the time, shared through music, magazines, and fashion, “gave rise to a horizontal web of solidarity that cut across the vertical ties to parents and authorities that had formerly isolated young people from one another and forced them to know their elders”(109). This had numerous effects, one of which was to amplify the attractions of various radical political ideas, by freeing young people from the moderating influence of their elders. (As Pinker puts it, “A sense of solidarity among fifteen-to-thirty-year-olds would be a menace to civilized society even in the best of times” (109).)

The boomers over time learned from their mistakes, became more moderate in their views, but most importantly, continued to play a dominant role in the culture, preventing the kind of radical disconnect from arising between youth culture and mainstream culture from emerging. That is, until recent years. The development of technology, especially social media, has given rise to circumstances that again mirror that of the 1960s, where the level of intragenerational communication occurring among young people completely eclipses the amount of intergenerational communication. And whereas during the 1960s, an official slogan was required – “don’t trust anyone over the age of 30” – to preserve the integrity of the horizontal relations among members of the cohort, the situation now is more extreme. Most older people are simple absent from the communications platforms used by young people. No one cares what they think, but often no one even knows what they think. Initially, this was due to lack of technological competence; older people just didn’t know how to use the tools. The pattern has been reproduced, however, because once the older generation acquires that competence, it makes the platform uncool, leading young people to move on to another one (the “your mom is on Facebook” phenomenon). Either way, the pattern preserves the supremacy of horizontal over vertical communication.

There are important differences, of course. The deviance of the ‘60s generation, and the subcultures that it spawned, were played out in the streets. Because media remained one-way, young people still needed physical space to assemble and interact with one another. With two-media media, social deviance can be fully virtualized, and so the countercultural impulse has moved fully online. Thus young people get caught up in cycles of interactive radicalization (most obviously, between the alt-right and the woke left) from the privacy of their own homes. Extremely subcultures develop, which every so often erupt into the real world, showing up in classrooms, or in the street, leading everyone else to wonder “what up with kids these days?” and “how did they get so weird?”

Good job alerts. Pass around.

Creative Art Director at Milk Street

I love Chris Kimball and everything he and team are working to build. Milk Street is a great example of next-gen Lean publishing, combining subscription media, commerce and premium content production (TV shows, podcasts and books). Milk Street is looking for a creative art director to lead its art department.

Engineers, Product and Design at Medallion

I am helping this amazing team reinvent the fan connection for a Web3 world. It’s a great group of people with an amazing mission — make it more fun and rewarding to be a fan.

Medallion is the connective tissue that empowers artists to launch web3 communities on their owned and operated properties. These communities allow artists to establish direct relationships with their fans and maximize the value of their work, free of algorithms, advertisements, and paywalls.

And… some high protein links:

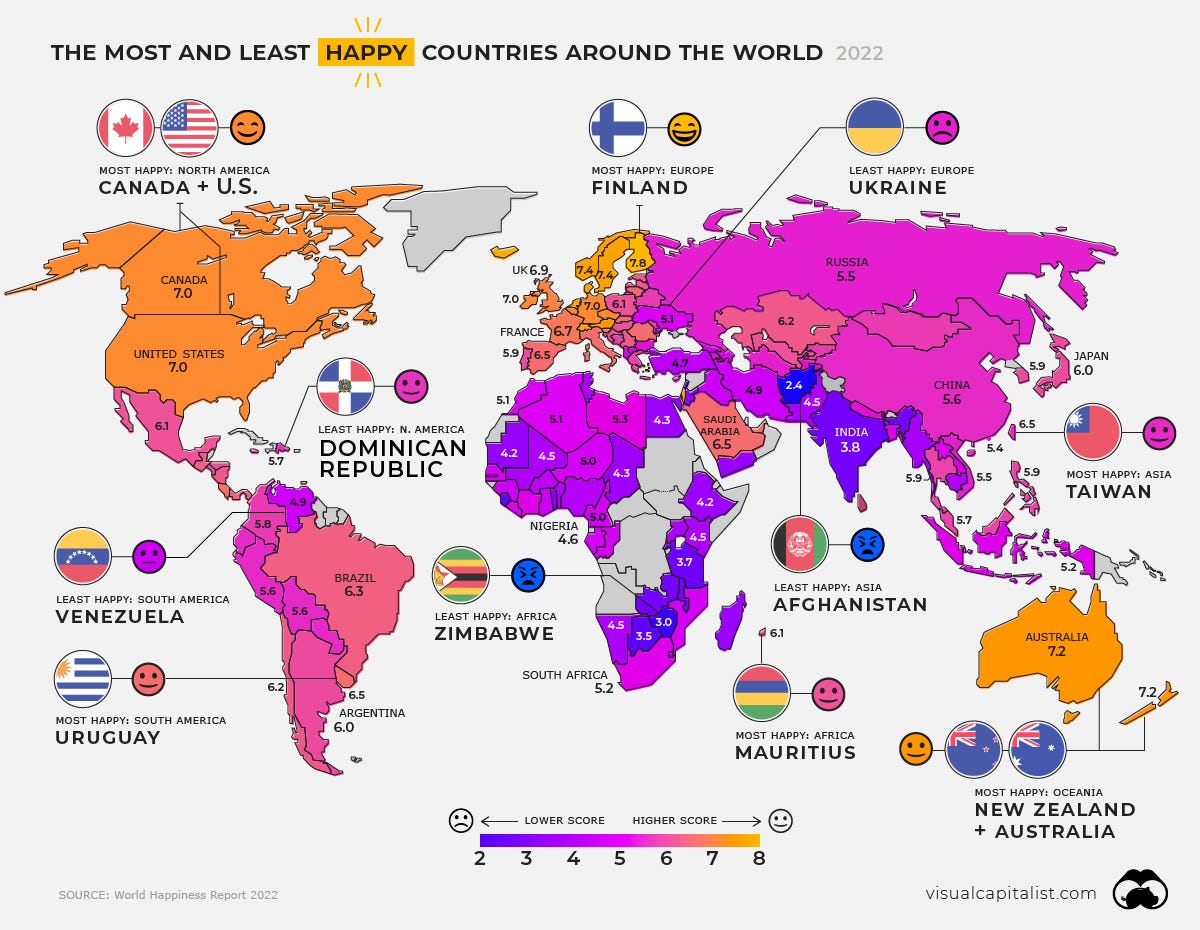

1. Behold, the most and least happy places around the world from Visual Capitalist.

2. If you haven’t already seen the Yuga Labs (Bored Apes etc) investor deck it’s worth looking at. Marvel at the margins from selling IP.

3. Related, Casey Newton on the confounding nature of ApeCoin and how decentralization is cool until it touches the core business. There’s something off about ApeCoin.

4. Want to run a small lean media business of your own. Buy a local newspaper.

5. Good perspective on where crypto is now. Ansem’s Q2 Outlook for the crypto markets.

6. A testament to ad systems persistent complexity, the recent kerfuffle at Gannett saw them sell billions of mislabelled impressions resulting in buyers thinking that impressions were running on USA Today but were actually running on Gannett’s small local publications, an internal error that persisted for 9 months and only surfaced when an independent researcher noticed the error. Perhaps an honest mistake. But imagine booking a hotel at a luxury resort in St. Barts, only to end up at an all-inclusive in Cancun. Not the end of the world, but disappointing. I can assure you that this is the tip of the iceberg.

7. Building and running companies is harder than ever. Can we stop running stories like this that include lines like: “Another employee said that on their last day at Glossier in 2019, HR didn't even bother to reach out for an exit interview.”

8. The Current Thing. Interesting POV from Strategery. Aggregation encourages consensus.

The end result is a world where the ability for anyone to post any idea has, paradoxically, meant far greater mass adoption of popular ideas and far more effective suppression of “bad” ideas. That is invigorating when one feels the dominant idea is righteous; it seems reasonable to worry about the potential of said sense of righteousness overwhelming the consideration of whether particular courses of action are actually good or bad.

Sitting in a park in Paris, France…