The Death of Impressions

How we measure the internet is changing. Lessons from China. An American super app. Repatriating the constitution. Fixing the Safari search bar.

Welcome to People vs Algorithms #6.

I look for patterns in media, business and culture. My POV is informed by 30 years of leadership in media and advertising businesses, most recently as global President of Hearst Magazines, one of the largest publishers in the world.

Get my weekly email here:

Wait… there’s a PVA Holiday Shop?

From CPM to GMV

The measure of digital media success is evolving from attention to transactional metrics.

When you evaluate a digital media property, you typically think in terms of attention: scale (number of uniques), frequency (daily active users), yield (cost per impression), prestige or quality (qualitative brand measures and associative benefits) or data value (authenticated users, profile value), position in a segment, search value etc. In short, the value and volume of impressions.

Impressions as relevant media measurement are dying a slow death.

They are being replaced by transactional metrics — the amount of goods or services sold, either someone else’s stuff or one’s own (including paid media itself). The internet is subsuming more of our commercial and financial existence and this activity is increasingly connected to media. Consequently, the model for thinking about media is shifting from “how many uniques do you have” to “how much do you sell”.

Attention metrics have traditionally defined media economics because they were the logical currency in absence of definable and transparent performance measures. They underpinned the mechanics of a media P&L: create content, generate views, ad impressions, multiply by price per impression, generate revenue.

Transactional measures, on the other hand, count the amount spent as the result of a media impression. This is typically gross merchandise value (GMV). When media is connected to a downstream event, as it is with affiliate revenue, it’s easy to track and get paid on the resulting activity.

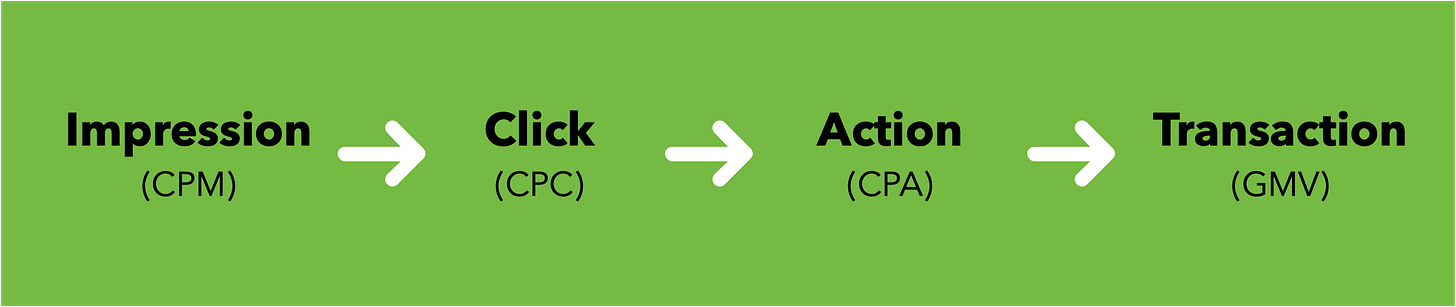

Performance metrics, like cost per click (CPC) and cost per acquisition (CPA), sit between impression and transactional measures. When a direct connection to a transaction is not clear, advertisers impute its value according to second order measures.

It’s worth noting that, despite many, many efforts to the contrary, selling digital advertising, be it display, native or social, has never successfully hewed far from a performance construct. We just didn’t want to admit it. Anything that has truly scaled has done so as a performance model, priced on click or acquisition. This would describe the billions of dollars that flow through programmatic pipes to Facebook or Google. While digital media continues to be sold on an impression basis (CPM), it’s a heavy-lift, direct sales model (advertising on Vogue) and a small percentage of the overall market. And increasingly marginalized.

Affiliate is simply the evolution of performance advertising. It has been around for a long time, but only really became a meaningful part of the media market with Amazon’s embrace and when e-commerce surpassed about 10% of total economic activity. The important measure in affiliate is, of course, GMV.

Subscription metrics like subscriber count and revenue per subscriber are closely related to a transactional measure, but here, you are measuring the value of selling your own product. It’s your own personal GMV.

Admittedly, some media will never be realistically connected to a transaction and attention measures will persist. This will certainly be the case with video advertising. Here you sell time. The consumption model lends itself to a time and reach based view metric.

Let’s picture the shift further out. More activity will be governed by transactions with digitally native currency on the blockchain. Virtual environments will be measured in terms of total economic activity.

When asked about the business model of the metaverse, Mark Zuckerberg described precisely this scenario:

I think at the end of the day, there’s going to be commerce, and I think commerce and ads are kind of closely related, because if there’s not any commerce, then there’s not much for people to advertise for. I think the first job that we need — well, I guess the first job is getting the foundational technology to work. Then after that, our next goal from a business perspective is increasing the GDP of the metaverse as much as possible, because that way you can have, and hopefully by the end of the decade, hundreds of billions of dollars of digital commerce and digital goods and digital clothing and experiences and all of that. And I think the best way to increase the GDP of the metaverse.

Who powers web GMV today

Stating the obvious, perhaps, three companies control traffic flows, the most valuable consumer data and therefore the machinery that powers GMV: 1) Google with intent 2) Facebook with identity and 3) Amazon with shopping.

Google is the engine that channels needs and desires — “what is the best dishwasher under $800” — to content products and, ultimately, to GMV. It’s hard to under-represent how dominant they are here. The chart below shows direct, search and social traffic sources to a range of content based web properties. The pink section represents search originated traffic, a market which Google monopolizes. While news sites tend to be less search dependent, it’s pretty clear Google controls the majority of web traffic, both paid and organic. As such they steer a significant portion of GMV.

Publishers may be the affiliate engine of the web, but they are the middle men, sitting between the search query and the transaction. The affiliate business does not exist without search. Nor does much of the digital media business.

Of course, search is the majority of traffic for retail as well.

As the main repository for identity data, Facebook is the engine of rich demo and interest targeting. The are extraordinary at connecting these data sets to economic activity. Increasingly the delivery of the impression and transaction are combined, as shopping functionality moves inside of their environments. Facebook advertising is usually bought on a CPC or CPA basis but from the buyers perspective what really matters is customer acquisition cost (CAC) and return on ad sales (ROAS), both directly connected to GMV.

While the charts above capture both organic and paid search traffic, they do not capture the importance of paid social activity, particularly for commerce brands. Despite an effort to diversify, most DTC brands continue to spend in excess of 60% of their ad spend on Facebook / Instagram (Modern Retail).

Amazon is the shopping engine of the internet and, consequently, sits on another extremely valuable data set — what you’ve searched, browsed and bought online. The ability to follow a consumer through purchase gives Amazon enviable signal on and off its platform. While Facebook and Google control over 50% of the US online ad market (eMarketer) Amazon's grew 87% YOY in Q2, 2021. Its market share exceeded 10% in 2020 at over $20B. To put this in context, Amazon’s advertising business is 8x the size of Snap’s entire business and nearly 7x the size of Twitter.

These players are so dominant, it’s hard to imagine what’s next. I think the answer can be seen in the emergence of digital payments. To get a sense of how this evolves, it’s useful to look at the rise of “super apps” in China and the success of WeChat as a case study.

Lessons from China

The open web is not a thing in China. The web is essentially “super apps”. Super apps are mobile applications that bundle a vast array of functionality around three pillars — identity, communication and, critically, payments. A super app like WeChat may have started as a texting solution, but today it is a place where you do everything from send money, pay bills, order food, get directions, follow influencers and brands, consumer content, translate text or stream live content. They have become the internet but with critical added utility — they are your wallet

The apps are a reflection of the number one power law of digital experience — build around the things that people do everyday. To wit, of the average 80 apps found on a phone today, nine are used with regularity (JP Morgan). The average number of apps downloaded by a consumer in a month is... zero (comScore).

So companies build mini apps inside of the super apps, piggybacking on the user graph and functional infrastructure. This, of course, creates massive power imbalances in the market complexities for governments around the world. Different topic.

The impact of daily life has been profound. Less than 10% of the country’s transactions are now made with physical money. 4 out of 5 transactions are made through WeChat and Alipay. WeChat is used by over 1.2 billion people and is the most important attention surface in the country.

China is home to the world’s largest social media market, drawing in an estimated 927 million users in 2020. The landscape has undergone dramatic changes in the past few years. At one point, it might have been easy to match each Chinese-born social media app to a Western counterpart. Such comparisons aren’t always possible anymore, as Chinese platforms have evolved in ways that have enabled them to leap ahead of Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

“In China, social media is deeply and fundamentally integrated with many other platforms, be that payment or food delivery or banking [or] navigating the city,” said Silvia Lindtner, a professor at the University of Michigan.

This transformation includes the birth of so-called super apps, one-stop platforms that allow users to easily partake in multiple activities—shopping, texting, transferring payments, and booking flights, to name a few—without having to switch apps

“WeChat is used for everything. It’s more than a communications app. It’s a payments app. It’s a news app. It’s everything,” Daum said. “It’s become its own sort of internet. It’s a little ecosystem of its own. … There isn’t an equivalent to that in the U.S.” (Foreign Policy, Nov, 2021).

WeChat’s simplicity and utility for businesses, small and large was instrumental in its growth. Companies get an official account within the app, like a mini website. From here that can post content and updates. Customers can pay for goods and services through the WeChat account. They can purchase ads to promote their offerings.

The use of QR codes is a defining feature of the app experience, representing an important bridge between the digital and physical worlds. Payments are facilitated this way — any merchant can post a QR code, or scan one, creating a simple, hardware free payment connection to the mobile wallet.

An American Super App

The point is, this has not been realized in the US. It’s happening now, but in a different way than happened in China. Here the field is far more fragmented. Starting points ranging from mobile operating systems to social media, payment and vertical solution apps like Uber.

Apple Pay and Google Pay are running at the opportunity from the mobile OS. But neither have built a dominant ecosystem around third party apps and importantly, merchants. They lack the experiential sophistication of the communication apps like WeChat, Whatsapp or Snap. They, like Facebook, face regulatory scrutiny that has made them gun shy.

We are seeing innovation in the opposite direction from P2P payments applications CashApp, Venmo and “buy now, pay later” (BNPL) offerings like Klarna and Affirm. The former have frequency and social relevance as a money replacement, the latter strength bringing together credit and merchant offerings, discounts and loyalty in particular.

Uber too is playing here, turning a daily behavior in ride hailing to food, grocery and package delivery and car rentals. Companies that have frequency and proximity to the credit card will look for ways to “super” charge the offerings.

It’s useful to reconsider our world in light of how time is spent in China. I ran a business in China and struggled to really comprehend the difference in digital distribution power structures. Understanding payments, how they power daily routines and the connection to the physical world is key.

Here the online journey starts when you buy tea in the morning and never really ends. The phone is permanent bridge between virtual and physical, between commerce, content and communication.

It’s pretty tough to determine the winners and losers here, too much is changing too quickly. Payments and wallets are lynchpin technology at the center of daily habit and key to the shift from an attention internet to a commercial one.

Have a great weekend…/ Troy

Other good things:

Related to last week’s note about banking and culture, on Tuesday MoneyLion announced the acquisition of Malka Media, a digital content, talent and marketing services firm. This is content to banking. I love the Malka guys and I am sure will do killer things here.

From Coinbase Q3 shareholder letter. The chart maps internet to crypto adoption. If it’s right, the gap is about 24 years. That would put the crypto apocalypse at about 2025. You still have plenty of time to speculate.

Gaby’s awesome Web3 Reading list. Get smarter about crypto stuff.

Post the iOS 15 release, I thought my Safari search bar was forever anchored to the bottom of the page. That is annoying. Turns out you can change it. Here’s how.

Help this DAO buy the constitution. Why not, it worked for Wu-Tang Clan.

The Chase report, Payments Are Eating the World is worth taking a look at.

And… the nice thing of the week thing.